The decision by the UK prime minister, Theresa May, to engage in talks with the Labour leader, Jeremy Corbyn, in an attempt to settle Brexit took everyone by surprise.

It cheered those seeking a soft Brexit, while enraging Leavers in her own party. May claimed she was forced to seek a cross-party compromise after failing three times to get her withdrawal agreement with the EU agreed in the British parliament.

Eurosceptic Tory backbenchers in the European Research Group (ERG), together with the 10 MPs of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), had voted with the opposition to defeat the deal May had negotiated. In looking for a cross-party solution, May hopes to sidestep the ERG and the DUP.

Yet there are doubts over whether anything will come of the May-Corbyn talks. Labour has its own Brexit divisions, with Corbyn, an old-style Bennite eurosceptic, leading a party whose membership is strongly pro-Remain. Labour supports a customs union with the EU, but one in which the UK would have a say. As an actual working policy, that is unrealistic. But as a party-management tool, it has successfully held Labour’s different Brexit tribes together by avoiding the need to take a hard decision on a genuine policy.

Negotiating with May risks causing a split between those Labour MPs who would back staying in the EU’s customs union (without a full say for the UK) and those for whom only remaining, via a second referendum, will suffice. While many Labour MPs representing Remain-voting constituencies in London and the South support a second referendum, others in Leave-voting seats in the Midlands and the North do not.

Officially, Labour backs a second referendum but Corbyn has done little to advance the cause. Consequently, there is an uneasy stalemate inside the party. The May-Corbyn talks could turn that stalemate into open warfare. While the shadow foreign secretary, Emily Thornberry, wants any deal that emerged to include a second referendum with “Remain” on the ballot, others in the shadow cabinet, such as the party chairman, Ian Lavery, are hostile.

A cross-party deal would, moreover, be limited to the government’s non-binding political declaration, which sets out the UK’s ambitions for its future relationship with the EU. May’s legally binding withdrawal agreement is not up for negotiation. The risk for Corbyn would be that he splits his own party and takes co-ownership of an unpopular withdrawal agreement. Any deal that emerged from the May-Corbyn talks would aggravate Labour’s internal Brexit divisions. For that reason, there must be a strong chance that the talks will fail.

Back to the House?

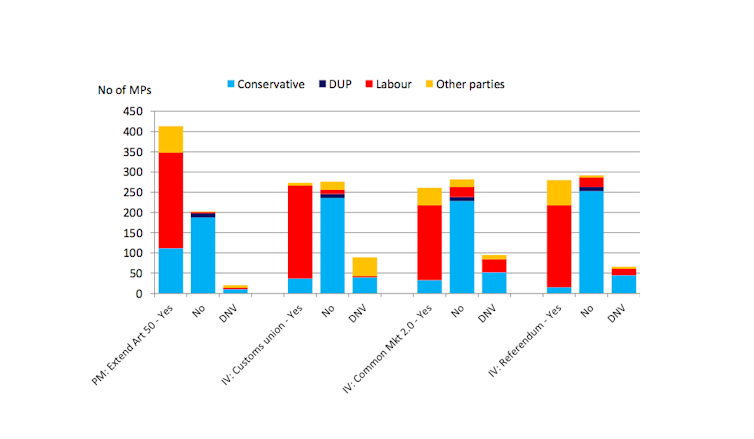

If the talks do fail, there could be a third round of indicative parliamentary votes on Brexit to settle the matter. Neither previous round delivered a majority for any option but if there were a run-off system of ballots, a winner would emerge. On the basis of the second round of votes, the most popular options were a customs union, single-market membership (“common market 2.0”) and a second referendum – although May’s negotiated political declaration with the EU would join any third round of votes.

At this point, May’s problem with her own party becomes clear. In the second round of indicative votes, Conservative MPs overwhelmingly opposed a customs union (236 against, with 37 in favour), “common market 2.0” (228 against, 33 in favour) and a second referendum (253 against, 15 in favour). The DUP also opposed all three proposals. Support came primarily from opposition parties. It stretches credulity to believe there will be a huge U-turn by Conservative MPs. If May tried to adopt any of them, it would be in the face of large-scale and intense Tory opposition.

Parliamentary votes on Brexit

One option that May seems to have ruled out is a no-deal Brexit. Yet that is precisely the direction that Conservative MPs have increasingly been heading. In the first set of indicative votes, 157 Tories backed a no-deal Brexit – over half of the parliamentary party. Reports emerged this week of a letter to May, signed by 170 Conservative MPs, calling for no deal. If May tries to force through a soft Brexit or a second referendum on Labour votes she could catastrophically split the Conservative Party, just as Robert Peel did over the Corn Laws in the 1840s.

A long extension

An alternative to a Brexit deal now is a long extension to Article 50. That also faces Conservative opposition. Fully 188 Tory MPs opposed the prime minister’s motion last month calling for just a short extension to Article 50, with the motion passed on Labour votes. Yet the likely success of Labour MP Yvette Cooper’s bill, which dramatically navigated the Commons by 313 votes to 312 on its third reading, would compel the prime minister to seek an extension if the withdrawal agreement is not passed by Exit Day on April 12. Parliament would decide what length of delay to request. The EU has most recently been indicating that it would be open to a year-long extension although May’s latest request is to extend just to June 30.

The EU would require a reason for granting a long delay – a “new political event”, as it has previously described it. That could mean either a referendum or an election. Tory MPs are strongly opposed to a referendum and most will be aghast at the thought of May leading them into another election after she lost the Conservatives their majority in 2017. The party would have to decide whether to include the withdrawal agreement in its manifesto. If it did, scores of Conservative candidates could end up signing pledges never to vote for it in its current form.

May’s cross-party switch might have appeared a bold judgement call. In reality, it was a desperate move that prioritises her withdrawal agreement over party unity. But Tory MPs are rapidly running out of patience and the government appears on the brink. There is talk of imminent mass resignations by ministers and even the prospect of some ERG MPs opposing the government in a confidence motion. There is a strong sense that we are approaching the moment when something has to give.![]()

Tom Quinn, Senior Lecturer, Department of Government, University of Essex

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.