It is only during the rule of the Order of St John over Malta that abortion, its practices and its regulation, start being documented. Before that, total silence seems to shroud the subject. With the arrival of the Knights, written records become more systematic and extensive. The fact that civil governance fell under the tutelage of a Christian religious order may help to explain why abortion starts being a subject of interest.

Though no documentary evidence survives, Christianity’s ancient aversion to the termination of unborn life, would, almost certainly, have been reflected in the criminal law of the islands even before the Order’s rule. But the first positive enactment I could trace goes back to Grand Master Jean Paul Lascaris who, in January 1650, by magistral edict, formally criminalised abortion.

The Grand Master prohibited any use of abortive substances and decreed that any member of the medical professions who prescribed them was liable to row in the galleys for five years, and those who made use of abortifacients would suffer public flogging and banishment from Malta during the Grand Master’s pleasure. The ban extended not only to taking those substances, but also to counselling abortion or aiding and abetting it. Cultivating abortive herbs led to a fine of 20 ounces of silver. This edict, strangely, only seems to criminalise chemically-induced abortions, but not those brought about mechanically, surgically or by trauma.

Our historians have unearthed several instances of abortion carried out during this period, a few more likely the product of hysteria or mental disorder. Contraception, though practised, was still very rudimentary, and unwanted pregnancies abounded. Most abortions, in fact, served as a delayed form of contraception.

The slave population seems to have been active in providing abortion services to those who required them. And from the scarce evidence that survives, these services were sought after throughout the social spectrum, from the nobility to the less privileged classes, from nuns to prostitutes. That evidence proves scarce comes as no surprise: abortion was universally regarded as illegal, sinful and shaming, and the utmost secrecy surrounded these practices.

One of the earliest records of abortions dates to 1647, in rather macabre circumstances. Gertrude Navarra (but actually Cumbo Navarra), still a teenager, residing in the monastery of St Ursula in Valletta, went spontaneously to Inquisitor Antonio Pignatelli, later Pope Innocent XII, to denounce her sins.

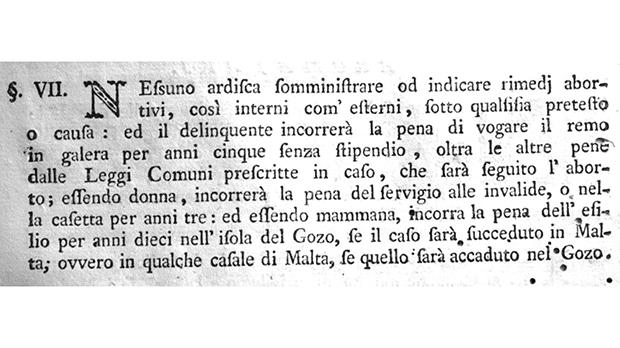

Grand Master de Rohan’s legislation banning abortion.

Grand Master de Rohan’s legislation banning abortion.For the past six years, she confessed, she had been enjoying sex with several men and with animals made available to her by Satan, in consequence of which she had to recur to abortions on a number of occasions, carried out by a certain Mariettina. Instances of this mixture of prurient self-delusion, Satanism and paedophilia are not unique in Malta. She named two of the men she frequented most: Luigi Corogna and the French knight Gianforet (Jean Foret?). She had also obtained a genuine human phallus which she used for her lonesome amusement.

The sad Gertrude was the daughter of the noble Andreotta and Lorenza Moscati and sister of Baron Ugolino Cumbo Navarra. She returned to the paths of virtue as a nun of St Ursula and eventually became the prioress of the convent on three consecutive occasions.

A later example is recorded in 1720 when the bishop’s court ordered the arrest of a female slave on the grounds that she was marketing a potion that enabled pregnant women to miscarry. This highly toxic concoction put the mothers’ life at risk. The last we hear of this slave, she is languishing in the bishop’s prison.

Frans Ciappara researched several cases of abortion that ended under the Inquisitor’s scrutiny in the 18th century. Such as the intimacy between the chemist Giovanni Angelo Sammut and Modesta Bravin from Cospicua. Modesta did not live up to her name and found out that she was pregnant. That is when having a pharmacist as a lover came in handy – “he gave her an abortive potion to drink”. And Grazia Saliba, widow of Salvu from Ħal Kircop, one day found out that her unmarried daughter Maria had fallen pregnant; the best she could think of to escape that shameful predicament was to seek the services of a baptised slave, Manuele, who gave her the right concoction and procured the termination of her pregnancy.

Veronica, from Birkirkara, rather than face an unwanted pregnancy, swallowed a dose of myrrh to miscarry, while the more gullible Rosa Mifsud, from Lija, barely 20 years old, took the word of the slave Sciman that if she put a piece of paper he gave her in a jug of water and drank it, her pregnancy would come to an end. The magic practice failed to work, and instead the hapless Rosa ended in front of the Inquisitor.

A nun of the Carmelite Order whose duties included accompanying visitors in the Conservatorio Gesu e Maria in Cospicua, got on friendly terms with a doctor from Żabbar who frequented the convent. Too friendly. They soon became intimate, and in 1730 she fell pregnant. To avoid scandal, Sister Catarina had, or tried to procure, an abortion. Her confessor ordered her to reveal everything to Inquisitor Fabrizio Serbelloni and she dutifully did, no doubt receiving condign spiritual punishment for the double iniquity of succumbing to the pleasures of the flesh and destroying a life ensouled by God.

An antique image of a surgeon performing a Caesarean section.

An antique image of a surgeon performing a Caesarean section.The slave population seems to have been active in providing abortion services [which] were sought after throughout the social spectrum, from the nobility to the less privileged classes, from nuns to prostitutes

A hushed-up scandal simmered in the Convent of Santa Scolastica in Vittoriosa. Persistent rumours pointed to the shameful behaviour of a group of nuns, together or on their own, directly in the presence of the holy images of Jesus and the Virgin Mary. In 1765, Sister Leonora Muscat, so the charge went, was having sexual intercourse with Satan, who had assumed a human garb to satisfy her carnal cravings. Sister Rosalta (Rosalia?) Mifsud and Sister Beatrice Muscat would talk between themselves of the lustful goings-on, until the convent gossip reached Inquisitor Angelo Maria Durini.

Anatomical drawing of a pregnant uterus by Leonardo da Vinci.

Anatomical drawing of a pregnant uterus by Leonardo da Vinci.Sister Leonora also had a mysterious pack of cards, and speculation was rife whether these had been given to her by her lover the devil, or whether she had made them herself under his instructions. As suspicion was mounting that Sister Leonora had got rid of an unwanted pregnancy through abortion, she was ordered to undergo a gynaecological examination to confirm or exclude this.

Another researcher who has been researching very thoroughly the antique parish registers of Siġġiewi and the Gozo Cathedral, has come across a large number of instances of women who aborted, or who died at childbirth, of premature foetuses baptised in the womb. These data reflect quite accurately the concerns of the civil laws and the bishops’ orders.

From Gozo, to choose at random, in 1666 the register mentions “una creatura abortita di nome Gioanne”, and a week later it mentions his twin sister Gratia. Grazia Bonnici had a “creatura abortita” in 1688; the following year a creature five months old “nata per aborto” was baptised at home by an unnamed woman; in 1691, the wife of Gio Batta Abela “morse d’aborto”; then Mario Aquilina was aborted on January 16, 1696, and baptised by the midwife at home.

Siġġiewi shows more or less the same profile. In 1708, Marius, son of Salvo and Anna Dingli, “natus abortive”. Maria Gatt had a “foetus abortivus” who was baptised by the midwife; Joanna Haxiach’s baby was conditionally baptised “in ventre matris”; in 1725, Angelica Psaila had a creature “abortisci nata”; after her, Margherita Mallia’s pregnancy ended in abortion and the foetus was baptised by the obstetrician. In 1791 it was the turn of Natalizia Borg to see her offspring “abortivus natus mortis”.

A botanical drawing of the Mugwort plant, said to be a powerful abortifacient.

A botanical drawing of the Mugwort plant, said to be a powerful abortifacient.Grand Master Emmanuel de Rohan promulgated his new code of laws in 1784, to modernise and update the previous Leggi e Costituzioni published by Grand Master Manoel de Vilhena in 1724. Rohan hit abortion through a two-pronged attack. Firstly, by a prohibition to cultivate abortifacient herbs: “No one shall be permitted to plant poisonous or abortive plants, under penalty of paying 20 ounces of silver to the Treasury, or under a heavier corporal punishment, having regard to the damage that will have resulted.”

The second provision is far more comprehensive. It deals with abortion from many aspects, though the drafting would, by today’s standards, appear quite woolly: “No one shall dare to give or propose abortive remedies, whether internal or external, for any excuse or cause. The delinquent will incur the penalty of rowing on the galleys for five years without compensation, besides all other penalties prescribed by the common laws for this, once the abortion has been carried out. If the guilty person is a woman, she will serve in the house of the invalids or the Casetta for three years. If she is a midwife, she will be exiled for 10 years to Gozo if the crime is committed in Malta, or to some village in Malta, if the crime is committed in Gozo.”

The Casetta, the hospital for incurable women, stood next to the Sacra Infermeria in Valletta, and it mostly cared for women afflicted by venereal disease, for which no effective treatment then existed. But this provision is not at all clear. What does it mean exactly by “besides all other penalties prescribed by the common law once the abortion has been carried out”? Would that mean that in case of a successful abortion, the penalty would be that established for wilful homicide? Does it also criminalise an abortion procured by a woman on herself, without external assistance? Four out of 10 for drafting.

To be concluded