The EU is pushing to have 40 per cent representation of women in boardrooms within four years to close the gender gap. Can this be achieved without the introduction of quotas? Ariadne Massa speaks to Centre for Labour Studies director Anna Borg and Malta Employers Association director general Joe Farrugia for their views.

Anna Borg

In 18th-century Europe, women who attempted to pursue an education were warned they would contract brain fever and risk sterility. Fast forward to recent history and the discrimination remains.

Photos: Matthew Mirabelli

Photos: Matthew MirabelliMalta had differentiated wage scales for women and men up to 1974, and until the 1980s women employed with the State had to stop working once they got married, bringing their career to a screeching halt

Discrimination against women is rooted in historical traditions that still permeate the subconscious of many decision-makers, who happen to be men and occupy top positions.

Centre for Labour Studies director Anna Borg believes these invisible barriers are behind gender inequality and unless positive action is taken nothing will change.

“Historically, discrimination was legalised and it’s no wonder we’re in such a pitiful situation,” she said.

The present scenario is really a pitiable one with just two per cent of women occupying boards in Malta – compared to the EU’s 17.8 per cent – and just 3.5 per cent making up board members of the largest publicly listed companies in Malta.

Unless we do something about this, change will be slow and we risk losing some of the best talent

These figures paint a dire picture that make achieving the EU’s 2020 target to have women fill 40 per cent of boardroom seats on publicly listed companies as likely as a third party being elected to Parliament in the next election.

Plus, even if by some freak turnaround this goal is reached, in Malta there are only 10 companies publicly listed on the stock exchange, as small and medium-sized companies are exempt.

This is where the maligned subject of quotas surfaces. Many feel they offend our sense of meritocracy, but Dr Borg says all data points to a state of fact – we do not live in a meritocracy.

So while the majority of both men and women surveyed for the Gender Balance in Senior Management Positions report felt these were not essential, Dr Borg points out that accelerated progress was achieved in countries where quotas were introduced.

“The majority are against quotas because very often people are oblivious to the historical background to gender inequality so they will say they don’t need to do anything as change will happen organically. “However, when you look at the statistics, progress has been limited and slow,” Dr Borg adds.

Accepting that women who successfully reached the top rungs of the career ladder were against quotas as it led to the descriptor of token women, Dr Borg insists that without a form of positive action and some form of sanctions Malta will continue to pay lip service to gender equality.

“Prejudice is still alive and women still face hurdles simply because of their sex. It’s impossible to swipe away historical traditions and the fact remains that 98 per cent of men occupy top board positions and women are being ‘tripped’ by the remnants of old boys’ networks.”

Did she believe there was a male conspiracy to discriminate against women or is it a matter of inherited unconscious habits?

“I think men still pull most of the strings. Most boardrooms are led by middle-aged men who have strong gendered assumptions and there remains the reluctance to change and share the power,” she says.

Dr Borg believes the numbers confirm that in 2016 the glass ceiling is still firmly in place and only some form of positive action and measures introduced by the government will crack it.

She stresses that she is all for equality and all-women or all-men boards are not a good idea. Balance is crucial to achieve a good mix of perspectives and experiences at the table.

A study in Science magazine showed that regardless of individual intelligence, women scored higher on social skills and when a board or group was gender balanced the tasks were more efficient.

“I’m not saying women are better than men; I’m just saying with everyone’s input the perspectives widen leading to better outcomes.”

Unless something is done she is not hopeful the 2020 targets will be reached in time, nor secured in the next decade as the EU approach was too soft for tangible results to be achieved.

“Studies show it’ll take a long time to break down the prejudices and tackle the root causes of male domination – women are burdened by caring for the family and men assume it’s not their responsibility.

Quotas alone, she insists, are not going to reverse the complex situation and Dr Borg says that the issue has to be tackled holistically on many fronts.

“Unless we do something about this, change will be slow and we risk losing some of the best talent.”

Joe Farrugia

Glancing at the empty chairs of the MEA boardroom, Mr Farrugia does not visualise men or women occupying those seats but simply capable persons.

He shrugs off the suggestion that there exists a conspiracy by Machiavellian men to purposely discriminate against women and strongly believes that talk of an old boys’ network is antiquated.

“I don’t believe there is a reluctance to open the door to the boardroom to women. What qualifies a person to sit on a board is experience and there are many qualified young women in their 30s who will very soon clinch these positions,” he says.

“The so-called old boys’ network may still prevail in some companies but it is counterproductive to be missing out on the available skills in the light of shortages in the labour workforce and downright stupid to exclude talent based on gender.”

So how does he explain the sorry situation where just two per cent of women occupy boards in Malta?

“I’m not disputing the figures and I accept that it is worrying and unacceptable but I don’t believe there is an active and deliberate culture to exclude women from boards,” he says.

Mr Farrugia is confident the grim situation will be reversed, especially since the latest Labour Force Survey shows that 78.6 per cent of women in the 25-to 29-year-old cohort were in employment; higher than the EU’s average of 66.4 per cent.

I find quotas humiliating. Women should be chosen to sit on a board based on merit, not their sex

This, coupled with an abundance of educated women – there are nearly 700 more female university graduates each year than males – clearly shows the talent is in the pipeline, so what is blocking the channel to the boardroom?

Mr Farrugia is confident these very figures will deliver the necessary changes and he is buoyed by the “rapid” progress witnessed where women are making their presence felt in managerial positions. He is happy to note that the MEA council is made up of 40 per cent of women.

“Nowadays, women are more ambitious and more focused. Even married life has changed and they rightly want to be more financially independent and manage their own careers,” he adds.

Mr Farrugia is clearly against the imposition of quotas at any level “as they don’t respect the people they’re intended to help”.

“I find quotas humiliating. Women should be chosen to sit on a board based on merit, not their sex.”

He admits that meritocracy may not necessarily be always present in the workplace, but he is against imposing draconian sanctions and is more in favour of long-term targets to change attitudes and culture.

One important change which he thinks will shatter the glass ceiling is when the roles of the family and the household are equally shared.

He points out that as long as more is expected from women to deliver on all fronts – the workplace and the household – she will face a situation where she will have to sacrifice her career, especially since in senior positions commitment is vital.

Unfortunately, he says, family-friendly measures were still perceived to relate to women, when in fact they were there for everyone to utilise.

He is convinced and hopeful the situation – coupled with increased flexibility for all, not just women, and more awareness – will be redressed.

While he says it is important for a board to have both women and men he is a firm believer that competence is the determining factor. Contrary to Dr Borg, he is not convinced of the argument that men and women have different qualities.

“If I were to examine my MBA students on a case study, should I give out a different paper to the different genders? And should I be expecting a different reply? In my opinion these arguments only work against women.

“I’m not a social scientist, so I’m not going to refute the findings, but I’d be very careful about attributing different qualities to gender. Competence is not gender-related.”

Quotas are not necessary

Imposing a quota to achieve gender balance in executive management positions is “not essential”, according to the majority of men and women surveyed.

Seventy-eight per cent of men and 71 per cent of women believe qualifications are more important than gender and imposing quotas limits the company owners and who can represent them (68 per cent men and 62 per cent women).

Interestingly, however, women have differing views on quotas when it comes to imposing legislation to achieve balance in boards – 48 per cent of women are in favour of quotas for boards in State-owned companies (33 per cent are against); but 38 per cent are against such imposition on boards in public-limited companies that are normally listed on the stock exchange (35 per cent are in favour).

Women are also equally split – 41 per cent – over whether legal quotas are the way forward in obtaining gender balance in the business sector as a whole.

Men are more consistent in their aversion to quotas on all boards – 54 per cent for State-owned companies and PLCs, and 59 per cent for the business sector as a whole.

The survey – prepared by KPMG for the University of Malta’s Centre for Labour Studies and done among senior managers in the 250 largest companies – will be presented during a Times of Malta business breakfast at Intercontinental Hotel, St Julian’s, on Friday. The event will focus on what is hampering balance in the boardrooms and what can be done to nurture diversity.

Men are more consistent in their aversion towards quotas on all boards

The Centre for Labour Studies wanted to spark a debate on the subject as the EU’s 2020 target to

have women fill 40 per cent of boardroom seats on publicly listed companies looms closer.

According to the global index Catalyst, quotas to increase the ratio of women in corporate board seats have been proven to work where introduced, but the issue is a contentious one as quotas lead to the assumption that women are there not because of their talent and ability but due to their gender.

To book, visit https://genderbalancemalta.eventbrite.com.

Findings on gender balance in senior management

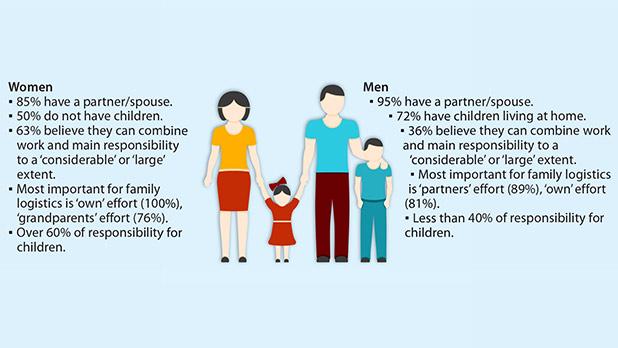

Profile of a manager

Profile of a manager Work-life balance

Work-life balance How to achieve better gender balance

How to achieve better gender balance Factors behind under-representation

Factors behind under-representation