Nowhere it is recorded if Caterina Scappi could read or write, but the part of her 1624 will by which she made manifest her determination to endow the hospital for women, is a little literary gem – perhaps not her own work but the notary’s: “As inspired by the Lord, eager to help and cure those wretched women who have fallen ill and who, bereft of everything, cannot receive treatment in their homes, driven by mercy for their misery.” She adds that some years back she had dedicated one of her houses near the Sacra Infermeria to their treatment and that now she needed a larger home and her attention fell on the house in the same area that had been Fra Giorgio Nibbia’s.

Scappi’s estate left an income of 400 scudi a year, a moderately substantial sum. It included the house at 138, Archbishop Street, whose rents had also to be used for the hospital. In time, after Scappi’s death, this income proved insufficient and had to be supplemented from other sources.

In the years after Scappi passed away, the hospital she had founded carried on growing until it reached a capacity of 300 beds, with the substantial enlargements made to it by Grand Master António Manoel de Vilhena. It is a pity that Scappi’s casetta was destroyed by enemy action during the war. The Evans Laboratories now replace it and not a single marker stands there in memory of the vision of this wholly extraordinary woman.

The many legacies left by Scappi in her three wills bear witness to her resolution to perform acts of charity during her lifetime, and even more, after her death. She thought of several bequests for the repose of her soul, she condoned the debts of those who owed her, left places in which poor women could stay for free, she gave them furniture, money, clothes and even dowries to enable them to get married.

The majority of those who benefited from her largesse were women, but sometimes a child made an appearance too, like Francesco servunculo (which means the very young servant or the servant tiny in stature) of her best friend the Magnifica Caterina de Loudun. Loudun was a small town in France that in 1634 had achieved international notoriety when it was reported that all the nuns of the Ursoline convent there had been possessed by the devil and had fallen into the most depraved ways, after their chaplain had signed a deal with Satan by which he made a present of them to him.

De Loudun appears to have been quite close to Scappi; in fact, in her second will, she appointed de Loudun her universal heir. The documents do not often mention her, but I found a 1625 petition by her to Grand Master Antoine de Paule about a problem she faced in the house where she lived close to the infirmary. Her residence shared an entrance in common with that of a servant-at-arms and when the owner divided the two properties, her half found itself without access. She petitioned the Grand Master to be allowed to open a door onto the bastions, and the Grand Master graciously granted her request.

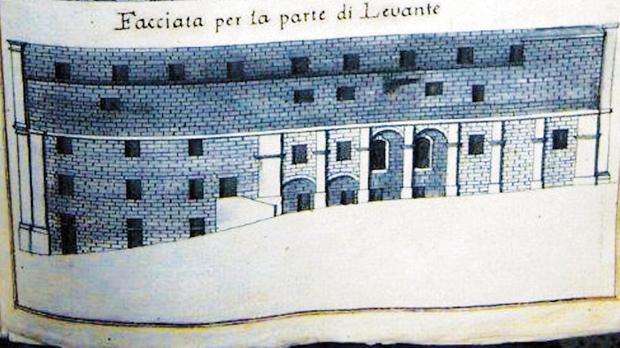

Unpublished rear view of Scappi’s Hospital for Incurable Women. Courtesy of the National Library

Unpublished rear view of Scappi’s Hospital for Incurable Women. Courtesy of the National LibraryThere is nothing to show that Scappi suffered from vanity or was a follower of fashion – her relentlessly plain clothes in her portrait attests to this – but her wills equally contain plenty of information as to what Maltese women wore 400 years ago. In her 1623 will she left Speranza, wife of Francesco Caniso, “una faldetta di raxia negra” from among those she had at home. Raxia was a fine, shiny, woollen cloth. In the will drawn up the following year she left Petrizia de Morlina “una faldetta di mezza raxia menata, un paro di lenzuola et un paro di camise”. Faldetta here very likely meant a skirt, not an għonnella.

The many legacies left by Scappi in her three wills bear witness to her resolution to perform acts of charity during her lifetime, and even more, after her death. The majority of those who benefited from her largesse were women

To her black slave Giuliana (eius serve ethiopis), among other legacies, she gave her freedom, una gramaglia (a black dress used in mourning) et palmi cinque di taffetano (five palmi taffeta, a luxurious and resistant silk, still in use today. Five palmi measured about a metre and a half). To her servant Domenica (Fenech) she gave a gramaglia with its mantle, while she left Speranza Caniso a gramaglia and five palmi taffeta. To Marietta Doneo and Marietta Santo she also willed five palmi taffeta each. And, in her last testament, dated 1643, she wrote in favour of Caterina, wife of Gabriello Alboranti, unum vestitum vellutelli et damasci – a dress in velvet and damask. The word vellutello is listed in Mikiel Anton Vassalli’s dictionary.

One of the legacies left by Scappi was in favour of Caterina, daughter of the painter Francesco Doneo (magister Francesco Doneo pictoris). This artist from Valletta, a son of Giovanni Doneo, lived in Pietà, and was married with several children. He was painting around Caravaggio’s times. So far we know next to nothing about him, except that he worked in churches and that in 1602 he found himself involved in a very serious case before the Inquisition, of which he was a familiar.

In the Rabat area, where he was painting in the cathedral and in the grotto of St Paul, Doneo took part in a duel when in the company of some prostitutes he frequented. He killed the other man. Conveniently, the Inquisition did not find him guilty of homicide, but of the lesser crime of adultery. In 1633, the painter sold Scappi a garden and some rooms in Pietà. So far, Doneo’s works as an artist have not been identified, and they must lie unrecognised together with the scores of devotional, primitive and provincial paintings of the early seicento that have still not received scholarly attention.

The same young girl, Caterina Doneo, beneficiary under Scappi’s will, also found herself involved in another set of Inquisition proceedings when architect Vittorio Cassar, son of Girolamo, who flaunted his virtuosity as a sorcerer, was summoned in front of the Inquisitor to answer to a charge of acts of witchcraft he was performing through the medium of the little Doneo girl.

Burial entry of Caterina la Senese in the parochial archive of the church of Porto Salvo, Valletta, 1643. Courtesy of the Dominican Friars

Burial entry of Caterina la Senese in the parochial archive of the church of Porto Salvo, Valletta, 1643. Courtesy of the Dominican FriarsIn consequence of her deals in real estate, buildings and loans, Scappi became quite familiar with Maltese notaries. But she also acquainted herself with Maltese advocates, as she left a legacy to Lucrezia, daughter of lawyer Palermino Montano U.J.D., and had lent money to lawyer Francesco Positano U.J.D. These initials stood for Utriusque Juris Doctor, doctor in both laws, canon and civil, then the distinctive stamp of professional lawyers. In these contracts, Scappi, though a woman, always appears on her own, without the assistance of a husband, a father, a brother or a curator. This throws light on the legal capacity of women to take part unassisted in contracts when they exercised acts of trade.

It appears that Scappi was well introduced in commerce, as there are in the Notarial Archives literally dozens of contracts that deal with guarantees, powers of attorney, transfers, receipts, buying and selling. But she also lent money against pledges or earnests. This we know as in her second will she included a list of debtors who owed her for the repayment of loans, and what the corresponding pledge was.

To the lawyer Positano she had lent money guaranteed by a catena aurea con un gioiello; to Aloisetta Montano, against un bucale (a jug) d’argento et una sicla (sicla, low Latin for a wine flagon) d’argento. Another woman, Argenta, without a surname, but habitantem in Manderaggio, had left as surety a mattress and uno brazzuletto. This is the first time, apart from maps, I came across the word Manderaggio in an official document.

Scappi was certainly wealthy, but shunned a life of luxury. As objects of any value she mentions that she only possessed un bacile d’argento (a silver basin) con un coperchio, quattro forchetti e tre cucciari d’argento. A rather early mention of the use of forks.

Emblem of the hospital of Santa Maria della Scala in Siena, which Scappi adopted as her personal coat of arms.

Emblem of the hospital of Santa Maria della Scala in Siena, which Scappi adopted as her personal coat of arms.In her last will, dictated on June 20, 1643, the notary recorded that Scappi was very ill in bed, though lucid in her mind. In fact, she died that very day. The one-liner registration of her death (or rather, of burial) which I managed to find in the Porto Salvo (St Domenic’s) archives in Valletta is laconic almost to the point of obscurity: “Today (June 21, 1643) Caterina la Senese from Siena, from our parish, was buried in the Carmelite church.” As at least 24 hours had to pass after death, this means she died on June 20.

This entry, again, avoids mentioning who Caterina’s parents were. The date does not agree with the one engraved on her memorial in the Carmelite church: 1642. But the latter is a clear mistake made when that memorial tablet was set up in 1791, or, more likely, when it was restored in 1877. I cannot understand why all those who have so far written about Scappi, assert that she died in 1655. This error keeps turning up.

By sheer coincidence, Scappi passed away when the Inquisitor of Malta was the prelate Giovanbattista Gori Pannellini, a Siena-born descendant of two noble families from Siena, the Gori and the Pannellini. He exercised his inquisitorial functions in Malta, rather questionably, from 1639 to 1646.

It is a pity that Scappi’s casetta was destroyed by enemy action during the war. The Evans Laboratories now replace it and not a single marker stands there in memory of the vision of this wholly extraordinary woman

As Scappi ordered, her remains are to be found in the church of Our Lady of Mount Carmel. On her death, she had been interred in the Carmelite church, in a corner of the chapel of N.ra Donna Dioria (I am not aware what this refers to. Perhaps a chapel named after the well-known sanctuary of the Madonna di Oria, near Brindisi? I have never came across any other reference to it).

But many years later, in 1791, the knight Fra Bartolomeo Mignanelli from Siena, official protector of the hospital for incurable women, feeling this obscure burial to be unworthy of a person who had distinguished herself by such outstanding charity, made arrangements for her remains to be exhumed from where they were, and solemnly reburied in a more prominent place in the same church. The lovely marble tablet we see today was then manufactured and placed on her new burial site, to serve as a memorial to Scappi, to record the transfer of her remains and the name of the knight who had wanted it all.

Burial memorial to Scappi in the Carmelite church, Valletta. Note that her coat of arms are taken from the above emblem. Courtesy of the Carmelite Friars

Burial memorial to Scappi in the Carmelite church, Valletta. Note that her coat of arms are taken from the above emblem. Courtesy of the Carmelite FriarsThat, at least, is the obvious reading. But the exhumation and reburial may well have been a move in the complex and rather bitter power game between Mignanelli and the Order of St John for the control of the Scappi foundation, a bruising controversy that eventually ended on the Pope’s lap.

What is certain is that Scappi would have disapproved vehemently of her remains being disturbed, moved and buried again elsewhere. In the will she drew up in 1624, she had ordered that she should be buried in the chapel of the Magdalene in the church of the Augustinians, on the express condition that, were her remains to be later moved, the Augustinians would lose everything they had benefitted in terms of her will, and had to return it all to her estate. She had also left a legacy for Masses in the chapel of St Nicholas of Tolentino, in the same church.

Was Scappi survived by any relatives when she passed away? So far we do not know, but in 1745 we come across a Marchesa Maria Maddalena Scappi, widow of Silvio Antonio Marsigli Rossi, in a contract of power of attorney. And, two years later, a Scappi is mentioned in another Maltese contract.

With the passage of time, the marble intarsia and the 1791 inscription suffered considerable wear and damage, as happens to all marble works placed on the floors of busy passageways in churches. When in 1877 a new marble pavement was ordered for the Carmelite church, the memorial and inscription were restored (with an error in the date of death) by Salvu Buhagiar. Today it is placed upright against a wall of the new church, as you enter on the left hand side.

From the fact that the remains of Scappi were buried (twice) in the church of Mount Carmel, one infers that she lived close by and that she had a particular devotion towards it. Her earliest will shows that Scappi started at first by being closer to the church of the Augustinians and its friars, to the point that she wanted to be buried there. In her various wills she always remembered all the religious convents of Valletta, without exception, and included with them that of Santa Maria della Pietà outsides the walls of the city (also belonging to the Augustinians). Apart from the church of Mount Carmel, she also left a separate legacy to the confraternity of that devotion.

It is fitting that a woman who understood so profoundly the Christian message of charity and expressed it so clearly and consistently, should be remembered not only on marble, but in our spirits too.

(Concluded)

Acknowledgements:

Thanks to Joan Abela, Alfred Camenzuli, Maroma Camilleri, Gabriel Farrugia, Christian Pace, Bernadine Scicluna and Theresa Vella for their inestimable help.